February 13, 2004

Reading, Reading

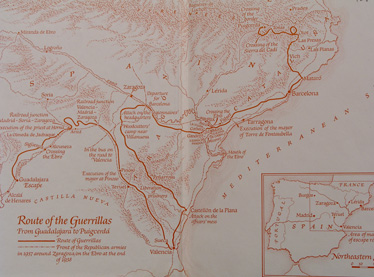

(Tossa is that little coastal bump North of Barcelona, below the words "Las Planas".)

I'm still working on "Art of Arts". This book by Anita Albus is built with many little brick-like chapters. I can chew off a brick every so often. It's the kind of reading you live with, instead of the type that makes you stop life as you burrow into its universe. (Of course, no aspersions to be cast on the burrow read.)

So, when we went to Half Price Books here in Dallas to sell off the weaker elements of our library (now herded into the boxes bound for Spain). I come away, buying a book: Thierry de Duve's "Pictorial Nominalism, On Marcel Duchamp's Passage from Painting to the Readymade".

So counterproductive.

Thierry de Duve's book is a reprise of the dogma that was administered to me in grad school. Now, dogma isn't all that bad... there's a strength that enables certain ideas to be elevated to dogmatic levels (which is the ruin of those ideas, ironically). But the basis of this book rests on the death of painting. Blah blah blah.

This is what they told me in school.

I shouldn't be so negative. Actually, the book is a good representation of the argument for painting as "painting". It's well written and cogent for that type of discourse. He's saying that Duchamp continued painting after he wrote "No more painting, get a job." He used industrial (readymade) products that were all around him to select as an alternative or an equivalent to his paint. He painted with everyday things within his reach, hence the frame-quotes: "painting". The world fit on his pallette, not just the pigment (that were industrially readymade anyway). A nice conceit for its' time, a time that had long legs. But it's an extravagant argument that has a shelf life (as all industrial products do). Is 82 years long enough?

I figure that painting had to "die" to find the other ways and forms of art that were destined to be seen in the past fifty years, the legacy of the PostModern. The era of the antihero. It's all fine and good, great art was made... but when they start chiseling it into syllabi....

It's as if in trying to see the stars near and bent round the sun, we blocked it out (I simulate this with my hand in the air, squinting), and what a treasure we have found! And then, after doing this for so long, our arms frozen in place, we forgot that there was a sun there at all or that it was just fine that we should permanently shade our eyes.

I was going to write that I don't know why I read it... but I can scratch for the reason:

Was I right to curl my lip so long ago?

Yes.

I've been tunneling into Brian Muller's "212121Painting", a recent article in Contemporary Magazine. A friend called to alert me of a reference of my name there. It's only a passing reference, and even though I would want to be thought of as a bigger contender in painting's debate, I am all too aware of my peculiar career trajectory. It's one that plotted a different course than what would have put me in a better position for this contention (such as moving to NYC after grad school). With a mixture of guilessness (not proposed here as a virtue) and idealistic overdesign (I mean, I had built a an insidiosly Pharonic educational substructure: a stout experience in the Navy and a complete architectural module as an art undergraduate educational substitute), I followed intuitively the track that would have me extablish an international support system first, and only then secondly the address the art (painting) conversation that seems to originate in the big city, NY. If you're going to take the road less traveled, you had better get used to being alone.

It is what it is.

Anyway, Muller's article is hard to read, but as jargon-stuffed inside painting/baseball talk goes, I admire the attempt. Muller tries to turn the page on the previous era and he's making a tentative bid on naming the next. For me, it is satisfying that he is recognizing that we are living in a different time, that a page must be turned. I've wanted to read stuff in this vein ever since the Berllin Wall came down. That was when I was leaving grad school in the beginning of the ninties. Every month, I expected to find a "where we've come and where we're going" article in the mags... to no avail.

And worse, no one wanted to talk about it. Among my friends and fellow artists in the mid-ninties, even the use of the term "PostModern" was bad form. Taboo. I mean, how can we move on without critiquing the previous era? You can be anti-Oedipus all you want, but sooner or later you have to kill your father (relax, Mom... I mean assessing the previous generation). I remember Lawrence Wiener's words: "We had to question the answers that were presented to us in school." I think my generation failed to do this after the end of the Cold War.

I can go on and on... and if I was to try to communicate an analysis of where we've come and project an idea of how to move on, it would take me the rest of the weekend and maybe a lot of next week to put the bones out there. Nuh-uh. That's for later... maybe. For now, I think my paintings say it in a nutshell. That's what they're for.

I was going to try to summarize what Muller is theorizing in his article, but I don't think I can get the lasso around his unruly herd of ideas. I have the mental image of mirrors facing one another and the image bounced endlessly within, and what I think he's suggesting is that there is no outside, and even the viewer is inside too. Here are his words:

"These 21 artists use this device through recontextualism to reverse the reflexivity from the reflexive artwork to the reflexive viewer. It is during the 'viewing event', within the tension between the assumed procedural structures of artistic productionand the viewer's cognitive structures, that the dialectic takes place- and the effort to locate structures generates transformations of those structures."

I warned you.

And now after the fatty, buttery-soft molecules of jargon and overstuffed theory, something to clean the pallette. Thanks to my good friend Stan Bertheaud, architect and writer in California. He sent back a book I gave him long ago. I usually give and forget, but this book has been coming up in my mind and I had to ask for it back to reread it.

Thanks, Stan.

As you can see, it's "Dark and Bloody Ground, A guerrila Diary of the Spanish Civil War" by F. P?rez Lop?z.

Let me transcribe a piece from the Introduction, written by Victor Guerrier (translated by Joseph d. Harris). Perhaps you will see what I mean by a clean pallette:

When I recieved the typewritten manuscript in Paris, a month after finishing my work, the narrative seemed admirable to me, crystalline in its absolute objectively. But that was the reaction of a historian. What would be the reaction of a sensitive reader, subjected to the ordeal of violence which is all the harder to bear in that it is not expressed in the narrative, but lurks beneath the surface of the writing on every page? Would not readers expect the author to break the unbearable tension of this unity between narrative and unspoken, ever-present violence, by indulging in the reassuring and familiar devices of subjectivity?For example, we worked on the terrible evocation of the crossing of the Ebro by the guerrillas. An orphaned child was with them and lost his life there. In the boat carrying them across, Fransisco's lieutenant, mortally wounded, found the strength to tell his leader that he, Franscisco, was not responsible for the murder of the child. As we read together the page where Franscisco had recorded this dramatic episode, he said to me, "When I heard that, my heart was relieved of a great wieght." But in his account, Fransisco does not say that. Already the enemy was running toward them. It was with his head alone that the leader could save the guerillas. He had to decide in an instant. And there lies the admirable truth of the account. The man who acts must remain outside all sentiment. Here is proof that the account was not written for a reader. The author never thought of him for a moment. It is I who think about him now. In delivering the book to the reader, I also deliver Fransisco to his judgement.

As we finished editing this episode and sat siliently contemplating the fire, Fransisco said suddenly, "Often in dreams, I see that child again." Nevertheless, I have added nothing to the primary text of his journal. In trying to justify the author, I would betray him. It would require all his admirable naivete to dare separate at this point the man who acts from the man who suffers.

"Sensitivity is almost never a quality of the man of great genius," wrote Diderot. "He will love justice, but he will exercise this virtue without reaping its sweetness. It is not his heart, but his head, that does all. At the slightest unforseen circumstance, the sensitive man is lost: he will never be the great king or the great captain. Fill the world of the spectacle with these weepers, but never place one on the stage."

One could not add to Fransisco's stripped-down text without altering it's truth. The art here is the abscence of art. Brice Parain, speaking from experience, has rightly said how for the combatant every word is false. No description is possible; reality for him is the moment of action and is foriegn to language. The analysis of the intellectual looking back on it is a lie.

(no offense to my intellectual and otherwise would-be intellectual friends. I don't think he was thinking of you.)

I've always felt that the role of talking about art is to use words like a lasso. You string them together to capture the art experience, rather than replace that experience with words. If "Art" is normally coupled conceptually with the term "Life", it's more that than they are opposites. I suspect it is because they share a similar quality. They possess vitality.

Art is life, framed in such a way that life might become more vivid to us. Maybe Muller is trying to suggest this in spades. It's just that the frame which at once-upon-a-time, was literal, became conceptual (literary?)... and over time, elaborate. Nowadays, I think it's best to keep it simple and look for the life that's sparked by canvas and colored mud.

Posted by Dennis at February 13, 2004 7:01 PM

I love this painting. A friend of mine gave me your cite. I am from Yugoslavia. Keep it up!

:))

jasmina

hmm

Hello jasmina, it's a pleasure to make your acquaintence.

Thanks for the encouragement!