June 10, 2013

Artist, Soldier (part1)

Preface: Artist, Soldier

I grew up within the military but I came of age in the art world. It all seemed perfectly natural to me until I emerged from graduate school. Most of the people that I've met in the art world seem to think that artists and soldiers are like oil and water. I'd like to shake that idea up a bit, emulsify it in a blog post.

My father was one of the first troops sent to Korea in 1950 to defend the Pusan Peninsula. He didn't talk about it when I was a kid, I remember only once where I was able to overhear a furtive account to his friends in the dregs of a party. It was only much later that I had learned more about his experience as PTSD overtook him so late in life. He reunited with a long lost brother in arms by the name of Captain Hughes, the officer in charge of his company. My father and about ten others were the sole survivors from a grinding massacre of about three hundred men. Papa re-enlisted into the Air Force afterwards and became a firefighter, runway air crash rescue. He said that he wanted to save people to recompense for the lives he took as a kid. I grew up knowing in my bones what Captain Hughes told me during my dad's waning hours fifty years after Korea, his eyes fixed on mine: "Your father... is a goddamned hero."

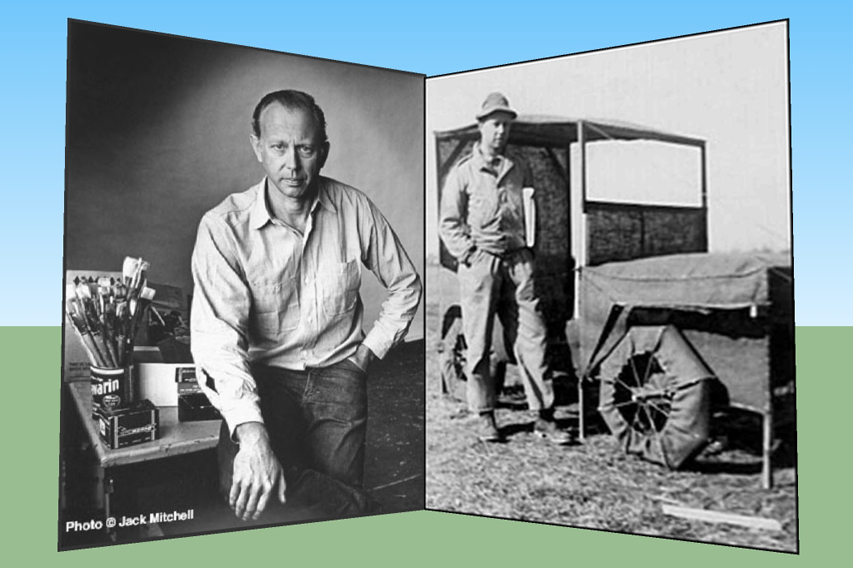

I was thirteen when I saw Goya's work in the flesh in the Prado and realized that art and specifically painting was my calling. This happened as my family traveled through Europe during one of our many globetrotting escapades. By that time I was already drawing, painting when I could, copying the illustrations in the margins of the art history books I was reading. Later as I graduated from high school, I joined the Navy as a rite of passage, a tribute to my father. An enlistment also gave me time to figure out my path afterwards as an artist. I was reading artist's biographies before and during my enlistment, it was commonplace and a comfort to find that more than a few artists I admired had spent time in military service. Recently, I had the good fortune of meeting one of these artists, Ellsworth Kelly, during his opening at Matthew Marks in Chelsea (no big shakes: a quick introduction by a mutual friend, a greeting and a handshake and that was it). Kelly is one of these folks: artist, soldier.

Kelly enlisted in military service during the WWII in 1943. He requested to be assigned to the 603rd Engineers Camouflage Battalion and later was transferred to what would be called the Ghost Battalion, based in Fort Meade. You can listen to Lynn Neary talk about Kelly's experiences on NPR's All Things Considered here. Greg Allen has a blog post on the topic too: Blowing Up Tanks: Ellsworth Kelly And The Camouflage Secret Army.

So, during my sailor days, I hatched my plan to substitute architecture undergrad for art undergrad, and go to art grad school afterwards. It wasn't until I got to grad school that I realized how singular my background would be. I enlisted just as the Vietnam War ended, my ship picked up refugees in the South China Sea in 1975. The rest of my service was pleasantly uneventful lots of training and ports of call. Since then, I've met only four other artists who had spent time in the military. Only one was a veteran of a war. Ellsworth Kelly's generation is fading fast. All of the artists in my cohort -from grad school to today- were not only unfamiliar with military service, but most everyone I met in the art community could not relate, a null set. I didn't solicit their opinion but when the topic of the military would arise on a rare occasion, conversations tended to curdle. Most didn't have enough of a familiarity with the subject to carry on a conversation, that's understandable. Some were mildly to strongly alienated from the soldier's life. A few --only a few-- were either disdainful or hostile, even.

It is to the latter groups of this mindset that I dedicate this blog post to. I have this notion that artists are like soldiers. I've nursed the idea for a while and now I guess it's time to take it out of incubation. But before I launch into an exposition of why I think that artists and soldiers share several important characteristics, I should clear the deck from the obvious reasons why they are different.

***

Prelude and a reality check: the counter-theme

Artists and soldiers are indeed different. They are dissimilar in ways that are profound.

Architects are like doctors, both share the spirit of the Hippocratic Oath, a responsibility to be conserving and protect their fellow citizens from harm, to be a force of growth and prosperity. Soldiers can be folded into this ethos, admittedly in counterintuitive ways. The assumption is that the protection from harm takes the form of force applied to the force that would harm one's fellow citizens.

Artists, not so much. Sure, we pursue beauty even to the farthest peculiar frontiers. Artists have flown the most hideous philosophical flags in this mission. Baudelaire's "There Flowers of Evil" is a ready example. Our aesthetic has long and justly embraced the idea that the turns of irony even unto the anti-aesthetic are integral parts of the warp of the warp and woof of the world. Danger arrests our attention. Like sex, it is a limbic first responder in our instinct for survival.

All art recuperates something from the dark side. That something is a cultural, civilizational product, the method involves aesthetics. Whether it's literature, poetry, painting, movies, even blogposts... all art deals in the part of life that indicates death. All of art trades on bad behavior (tracing forwards from Upanishad and Homer), and the chronicle of history proves this. Mike Kelly, Robert Mapplethorpe, Jason Rhodes... the list goes on, only a few of a significant population of celebrated artists from Alfred Jarry onwards, all delved deeper and ever more boldly into the dark side. Artists go there. Artists go there, the good ones at least, in order to recuperate value from loss.

An artists' action has never legitimately put the lives of its audience in actual danger, every idea is theatrical. The defense is that art exists in the realm of the imagination, which knows no bounds. The erasure and re-delineation of boundaries is the history of art world (in the West) and today, the impulse to redraw the boundary that defines art is not so strong. The ability to maintain the distinction between imagination and reality might be the best definition of sanity. Sure, the adventure of blurring the boundaries is exhilarating, but it can also be frightening as well.

Soldiers are an organized force. Artists are a disorganized force... or it might be better to say that artists are organized after the fact. Their energy is divined, patterns are searched by the intelligencia after the moment of creation as the first drafts of history are written in the museums. Soldiers train repeatedly until the routines of attack and defense are imprinted in muscle memory so that when the fog of war arrives, they can do what they have to do in the midst of chaos. The widening site of art production is pure chaos at the moment of creation. Especially now when the population of the art world is gargantuan, artists are churning a froth of creative acts which is sorted out more or less by the conventions of exhibition protocol, and historians survey, chart and rank the emerging landscape into an intelligible order.

Society organizes an armed force to protect itself and therefore soldiers begin their service with a vow to protect the constitution, the literal social contract. Artists, not so much. There is no explicit social contract for artists to serve. Artists are more like pirates in this respect. Now, even pirates have their codes of conduct, but like it is in the social world of artists, any such code is at the very least provisional and radically open to interpretation.

I'm thankful that I've only heard it said that war is boredom punctuated by horror. I can testify by experience to a correlate saying in the military: hurry up and wait. Could we say that art is the inverse of these? Is art horror punctuated by boredom? Do we not wait and then hurry up? Life in the studio is like a horror in the flux of uncertainty when we push ourselves to best others and even ourselves, not knowing how we will, if we will figure into the tale of history. And just as any artist is familiar with the frantic run up to an exhibition, there is the strange sense of having been emptied out, your guts on public display and there is no time left to improve one's aspect. Afterwards, there is something like boredom, where the last body of work has won all of the minds it could and you are left with a fresh blank page of history, your emptied studio turned out before you as you begin again to re-pump the pressure to reacquaint yourself with the demand to remake yourself anew, to be able to surprise yourself and everyone else yet again.

***

Ruskin: "No great art ever arose but in a nation of soldiers."

***

On narrative and conflict... Charlotte Higgins on Love and Greats:

"What's interesting is that The Iliad is the first book, and it's about war. Why is that? I've got a funny feeling that war and narrative are tightly bound together. Both narrative and conflict are the products of civilisations. Once you start building cities, having private property, creating hierarchies, etc, then the inescapable fact is that conflict will occur. And conflict is the stuff of drama, of stories."

***

What artists should learn from this: that art is hazardous duty.

***

Sailor or pirate?

And a symbol for "danger." (The skull-and-crossbones design would come in handy when Jobs issued one of his infamous motivational koans to the Mac team: "It's better to be a pirate than join the Navy." Painted on a flag, Kare's Jolly Roger was hoisted outside of the Mac skunkworks...)

***

"To have the arts of peace, but not the arts or war is to lack courage. To have the arts of war and not the arts of peace is to lack wisdom."

-Hayashi Razan (1583-1657)

***

Two weeks later, Jesse would be cut down by small-arms fire in Baqubah. He would survive some time before passing away. I could not possibly avenge him; I was two thousand miles away. I heard about his death in the most undignified way: a MySpace bulletin read in an Internet cafe in Rome.-Army of Dude: a blog from an Iraq War vet

Coming back to Iraq after leave, I looked at Jesse's assault pack a lot differently. I still carried it with me everywhere, but I treated it a lot better. I no longer tossed it off the Stryker into the dust. I didn't shove it into small spaces on top of the vehicle. In the outposts where we lived, I used it as a pillow.

The assault pack is not an assault pack anymore. It's a backpack. I no longer stuff it with extra grenades, ammunition magazines or packages of Kool- Aid. It now carries textbooks, calculators and pencils. I started my first classes a few months ago to fulfill the plan two years in the making. I imagined it to be a seamless transition into civilian life. Boy, I was f------ naive, even when I came home. I saw some guys falling apart from PTSD, getting drunk or doing drugs to drown it out. I thought I made it out okay, relatively.With my unassuming tan backpack at my feet, I break out in a sweat if I even think about mentioning Iraq in the classroom. I let it slide nearly every time, yielding the topic to daftly opinionated classmates. I feel like a foreign exchange student, confused about the motivation of my peers. I literally carry the burden of readjustment on my back, not wanting to let go my past but anxious to get to the future. Fractured into part war veteran and part journalism student, who I am speaking to determines which part of me is actually there in the room. To many, my past is my best kept secret. For all they know, my parents pay my tuition and do my laundry. I can be honest here. It's terrifying to be honest out there. Perhaps it's best that way.

by Alex Horton

*** Posted by Dennis at June 10, 2013 1:12 AM

Leave a comment