February 26, 2019

What are we seeing?

I'm delighted to read John Mendelsohn's review of my show at Galerie Richard in ArtCritical. Precise, distinct and insightful. I'm especially pleased since David Cohen is the publisher and editor of ArtCritical, and the host of Review Panel. I consider Review Panel to be the best venue of live art criticism in New York City, bar none. In these events, one can hear writers think on their feet and the event is quite open with Cohen involving the audience in the give and take of opinion. Close readers of this blog will find many notes that I have taken at Review Panel events over the past several years.

I'm burgeoning... with gratitude.

Building Up and Breaking Down: Dennis Hollingsworth at Galerie Richard

by John Mendelsohn"What are we seeing?" That is the fundamental question that always seems to bedevil us when we look at risk-taking art. We are asked not simply to experience a work but to intuit a whole constellation of intentions: aesthetic, ideological, and poetic. In the case of Dennis Hollingsworth, we have our work cut out for us, in spades. That is not to say that the effort to know his work is a slog - far from it. In these paintings are delights and conundrums, both brain-twisting and eye-popping.

There is an antic, psychedelic spirit at work in the eighteen pieces which comprise this exhibition. Hollingsworth arrives at the derangement of the senses via multifarious stimuli - stylized organic ornamentation, phrases spelled out in large letters, intense patterns, and paint, marbleized and in thick, dripping impasto. These and other motifs are layered in compositions that seem joyful and fraught in equal measure.

The works - primarily paintings, along with two wall pieces, and a sculptural vitrine - share a dimensional quality, both in their construction and their surface treatment. This projective thrust is central to Hollingsworth's project, a baroque celebration of painting's capacity to impinge upon our space and our consciousness.

Among the most intriguing of the pieces are the constructed paintings, including So That We Could See (2018), a white convex form, like the sectioned canopy of an umbrella, covered with the words of the title, and thick skeins of paint. The effect is a praise song for vision itself. The same spirit animates Dazzling Treasures (2018), which has ten circular panels, each like a separate screen or a unit of an insect's compound eye, displaying blossoms, webs, drips of paint, and words, including STARS, SUN and WE.

Looking Back to Look Forward (2019), is quite a production, a kind of theater set of paintings within a painting. Easier to apprehend than to describe, this work begins with an abstract shield-like form, in front of which projects an array of ovoids with thick or flowing paint. Ensconced above the main forms is a miniature version of the painting, like the artist's original thought presiding over the completed work. The painting's elements are attached to a wood scaffolding that is curiously neutral and functional in a work whose elements are otherwise so thoroughly active.

Perhaps the best way to read the built support is to see it in terms of the modernist grid that informs many of the works in the exhibitions. The painting's title reminds us that Hollingsworth is scanning the history of the past century's painting, picking up signals from stars, both nearer and more distant: Matisse in the leaf and flower forms, Pollock in the use of paint as its own living corpus, Ryman in the appeal to conceptual rigor, and Lawrence Weiner in the cryptic language.

But beyond any received wisdom, these paintings possess an

essential originality and weirdness, in the best sense. They seem to allude to an intense awareness, where touch and vision are at play together. In Deep Body (2018) the crenelated black oval, filled with shivering lines and dark forms, reads like a tantric embodiment of this state of inner harmony. In this heightened condition, building up and breaking down appear as equally desirable. In We Are... Secrets (2018), a field of red and yellow lines has been eaten away, leaving a star-like neural network, behind which is a band of letters, the partially visible title.The painting Square Cube (2019), is a high-style vamp, with an array of the artist's favored elements of leaves, words, and elongated asterisks mostly covered by engulfing waves of red, studded with extruded paint that resembles spiny sea urchins. This painting, although recent, seems to hark back to some of the earlier works in the exhibition, displayed in the back gallery - such as Minerva's Serpents (2015) and Limitlessness and Strange Desire (2015) - with their extravagant, totalizing approach to a continuous field that is continually being interrupted.

There are two possible hints of the direction that Hollingworth's recent work might open up. The sculptural wall reliefs, Laocoön (2018) and Second Order Revelation (2018), both make manifest the wood support hidden in other works, here functioning like a cross upon which is screwed the living body of looping lines of canvas. A second path is displayed in the painting CMB (2018), which suggests a via negativa, a way of knowing that rejects the material certainty of Hollingsworth's mostly emphatic works. Here we see what seems to be a truncated mandorla, an almond shape that recurs in religious art, composed of wisps and phantom residues of paint on raw canvas, apparently the result of multiple off-printings of an empty sperm-like form. It is as if a tender, existential recognition has unexpectedly made itself known.

Dennis Hollingsworth: Pushing paint and painting

I'm honored to be the subject of a review at Sharon Butler's Two Coats of Paint blog, written by fellow artist Riad Miah. Read the whole piece, follow the link to see the article, complete with the accompanying images of paintings in my solo show at (Galerie) Richard, 121 Orchard Street, LES, NYC, up until March 9th, 2019.

Contributed by Riad Miah / Dennis Hollingsworth's exhibition "Burgeoning," the artist's first solo show at Gallery Richard on the Lower East Side, comprises conventional paintings from as early as 2014 and newer ones that move decisively into three dimensions. Without adding solvents, Hollingsworth massages paint from the tube to a creamy consistency and then applies it with custom-made tools. It is squeegeed, dragged, flung, and sculpted. The paint coalesces into forms that look like spores, starbursts, and other organic entities. He uses stencils to create leaf-like shapes, stripe patterns, and letters that sometimes become words. The paint is so thick that some canvases - for instance, Minerva's Serpents and Limitlessness and Strange Design - employ supports and structures to accommodate the paint, and thus suggest low-relief sculpture. The newer pieces bring to mind other artists whose work also investigates the structure and support, including Molly Zuckerman-Hartung, Elizabeth Murray, Ron Gorchov, James Hyde, Rosy Keyser, and Fabian Marcaccio.According to the press release, in the 1990s Hollingsworth was deeply engaged in the "painting is dead" conversation, which today seems every bit as overwrought as it generally was. Nevertheless, Hollingsworth still takes his mission to be figuring out what painting is and what it can be, searching by way of images, object, and text. A good example is Tear It Wide Open. The painting is shaped like a cartoon rendering of a head with ears that jut out at the left and right sides of the picture, reminiscent of Homer Simpson, Charlie Brown, or Tin-Tin. The painted passages resemble an aerial highway, and the piece incorporates an eye exuding feathers simulated from canvas. Perhaps Hollingsworth is suggesting that the painting is capable of flight or vision.

His new work involves letters and text, sometimes intelligible and sometimes not. In a fairly clear nod to Mel Bochner's paintings, Hollingsworth's textual pieces allude to the process of creating art but also contradict the materiality of painting. He also goes a step farther, literally stretching language. In So That We Can See, the surface of the painting is pushed out of the two-dimensional plane of the canvas, distorting words and phrases nearly to the point of incomprehensibility. The net effect is that the work's verbal and visual components compete with one another, barring the emergence of a clear hierarchy and affording the work a kind of unstable dynamism. This is adventurous art, and far from dead.

About the Author: Artist and educator Riad Miah was born in Trinidad and Tobago and now lives and works in New York City. He has exhibited with Lesley Heller Workspace, Rooster Gallery, and Sperone Westwater Gallery, among others.

February 19, 2019

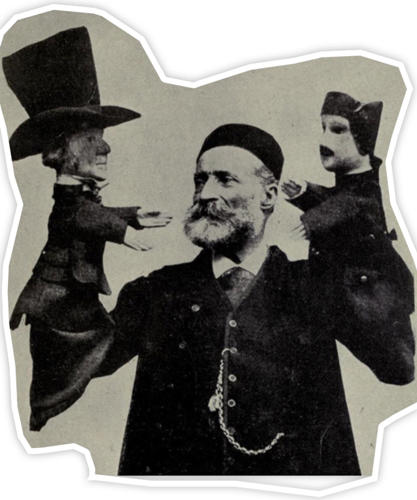

21st Century Janus

I've just hammered out an essay intended for a collaborative book project which is focusing on contemporary painting in Southern California. Even though the subject centers on SoCal, the thesis applies to painting in the world at large. Seeds for this are strewn throughout the entire history of this weblog and the image above is repeated from a tweeted manifesto last year, suggesting the linkage. It's a war wagon, meant to bring peace to warring factions and unify the schizoid split inherited from our 20th century.

3,210 words and 23 paragraphs below the fold...

Painting is the Sun

To see stars nearest the sun, you need an eclipse. Painting is the sun, but in order to see the stars adjacent to it, we had to occlude it as if we had blocked it with our hand outstretched. We discovered a multitude of stars: installation, performance, social practice, conceptual, video, film, the list is seemingly infinite. This is good, this is progress. The art world, like the sky is richer now that we know this. The sun is also a star like any other star in the universe. By size and magnitude, it's actually quite average. Similarly, painting is co-equal with the multitude of genres now celebrated in the universe of art today.

This was an image that I had conjured about ten years after I left grad school. I was trying to account for the apparent force of Critical Theory during the late 80's. I was trying to understand the proscription against painting and the near universal yet silent rebellion against all of this in grad school studios all over the world and especially in Southern California, when young artists ignored the warning that painting had died. The constant message was that it was a relic of a past best left interred.

Painting resumed living despite the forecast of its death. However, it had never addressed the reasoning regarding its expected demise. Postmodernism is the name of this pain. Back in the Los Angeles of the 90's, I remember finding it hard in social settings to discuss this umbrella term, postmodernism. Friends found it distasteful to summarize what they considered to be incommensurable. For them and for most of the world, the current era was like the infinite ratio of an irrational number and it was in bad taste to profanely circumscribe its sacred inscrutability.

Perhaps it was my background, my first degree in architecture that made the difference? The taxonomy of aesthetic movements in architecture is more structured than it is in art. To define postmodernism, one had to define modernism, to define modernism, one had to define classicism, and onwards down the line of turtles towards and past the archaic. Architects have the advantage in this regard. The view of art history along the aspect of building science renders modernity much more clearly than in art. Roman engineering had amplified the classical Greek canon and convention remained tradition for centuries undisturbed until the Enlightenment's cycle of scientific and industrial revolutions had upended the apple cart with a whole host of new materials and methods of construction. To be modern is to reconcile the thing one makes with the life one is living. This became crystal clear when factories, railroads, telegraphs, bicycles, airplanes, and reinforced concrete appeared, disrupted and were in turn disrupted by newer innovations. Modernists were bent on redesigning a new apple cart, postmodernists knew that all apple carts are destined to remain upended. Modernism was bent on saving the world. Postmodernists ridiculed and embraced the futility of such ambition. Rupture, dissolution, entropy and disorder is the new order for the latter, the new system was an anti-system.

We tend to think that the sequence was first classicism, then modernism and then postmodernism. But the modern and the postmodern arose Janus-faced as one at its inception. This is clear in the accounts of turn of the century Paris, in books such as Roger Shattuck's "The Banquet Years", which spotlit artists such as Picasso and Alfred Jarry as avatars for modernity and postmodernity. Let's now define the undefinable. Modernism tried to touch G-d via material means. Transcendence. Postmodernism pointed to everyday life via conceptual means. Quotidian. The New York School of Abstraction was the high tide of modernism, no artist could get closer to G-d than did artists such as Pollock and Rothko. Young Rauschenberg and young Warhol saw that they couldn't extend the existing dialog, so they flipped the script. Postmodernism proceeded in concatenating waves: Pop, Minimalism, Conceptualism; each dialing down materiality, each referring to everyday life, each focusing on information content. These were many ancillary movements, superpositions of trends, but all pointed to the world conceptually.

The fruit of the conceptual tree was Sol LeWitt's art-as-a-set-of-instructions, the epitome of dematerialization. Sol LeWitt and the conceptualists did what art should do, clairvoyance. They intuitively anticipated the approaching epoch, in our case, the Information Age, ten or twenty or thirty years before it had become manifest. After 1968, art moved through and past an achieved objective. Like a river that begins as dew forming from mountain mists and dropping into icy creeks splashing down over rocks, fusing into rivers beginning fast then growing slow and increasingly muddier until fanning out, creeping into a delta to the sea... finally oozing... stinking... fetid... vaporously disappearing into clouds... so too history and especially art history. The past fifty years have been a spreading delta driven primarily by Critical Theory, the ultimate conceptual index of a ubiquitous, increasingly politicized world. It has been a long run, with some eddies and counter-currents along the way.

But today, this postmodern engine has been running on fumes. One tell-tale sign is the appearance of the zombie. Coined by Martin Mugar and popularized by critics such as Walter Robinson, this meme captured the questionable quality of art that arose in synchrony with wealth disparity and the evaporation of the middle market and class. Zombie Formalism looked like great art but only in fading echoes of pale imitation. Mugar nailed it in his 2014 essay: "...These works of art look like paintings, act like painting but on closer inspection are as bloodless and lifeless as zombies. That the New York culture allows this kind of painting to rise to the top is no surprise: the New York financial world is known for creating zombie loans and the NY Fed has succeeded in creating a zombie economy".

We are today obliged to account for the etiology of the Zombie in early 21st century culture. How did this come about? I trace the inception to 1991 after the Berlin Wall fell, when the Soviet Union collapsed, when Critical Theory had reached its apogee in the academy, when it became crystal clear that the 20th century had ended a decade early. In the months, then years afterward, no articles appeared in the art press to conduct the necessary overhaul critique of the 20th century, of modernity-cum-postmodernity. We had the responsibility to collectively evaluate what could be relevant and what must be considered irrelevant to the looming 21st century. We declined our responsibilities. We, in effect, whistled through the graveyard.

Frances Fukuyama wrote "The End of History and the Last Man" in 1992 and in effect, declared Western liberal democracy the winner of the evolution of world civilization. Various interpretations of Fukuyama's essay-cum-book ensued subsequent to its publication, but its enduring impact had been deep and widespread. The system that had brought us to this place in history and had prevailed needed no further modification. This was no less true for the art world as well. Postmodernism was just another way to say Western liberal democracy. The end of history was real for the art world. Artists and especially new generations of artists need not bother with writing the subsequent chapters of history. Only art that emulated bibliography and end notes in some way however oblique were acknowledged. The ground of this self limiting condition was well prepared in advance. G-d was declared dead. Truth. Originality. The author. Painting. All dead. Anything one could say has been said before and woe to those who don't acknowledge it via citation and pale imitation. Nothing new could be permitted, so declared the descendants of the "Shock of the New". And so in time, nothing like the new was attempted.

Even when the reminder of the weaknesses of our existing Western liberal order presented itself in the suicidal take-down of the twin towers of 9-11 when rival ideologies challenged and attacked our complacency and exposed rivals within the world order, we simply shrugged and continued whistling through our own graveyard. A stasis of order evacuated the mind and the zombie arose to mock us all. Painting was dead and lifelessness was the only card... or role left to play. As the fruit of the postmodern tree was plucked (Sol LeWitt's art-as-a-set-of-instructions), painting was obliged to play second fiddle so that a new age could be born.

In order to account for the preeminence of painting in art history, one must concede that like the sun, painting is closer to our lived experience than the other stars. We feel its warmth infinitely more keenly than we do from the light of other stars. Immediate, accessible, concise in its component nature of pigment, binder and solvent. Painting is a complete correlate to our visually dominant mental world in terms of psychological theories of perception.

Painting acknowledged this artifice at the initial spring of the arc of postmodernism. Frank Stella started painting within bounded systems, so too did Jasper Johns with his flags and later when he buried this inherent limitation within his taciturn facture. Rauschenberg famously erased DeKooning and when he later romped in sheer visuality, he subordinated painting to printmaking and transfers. Warhol, like a number of his fellow peers used the design arts preeminently to dislocate painting. Greenberg's Post-Painterly Abstraction and later variants including Neo-Geo were determined to find a correlate in painting that also turned the minimalist dial downwards. Initially, it had to be thus. In the face of the cultural sea change of the emergent postmodernism, not only were there interesting avenues to explore in paintings' own negation, to do otherwise would have been surly and bitter. But twenty years after the announcement of the death of painting in the 70's when Critical Theory had crested in the academy, when the Berlin Wall fell and the Cold War ended, art faced a crossroads. It was obliged to examine the nature of the artifice -the entire postmodern project, in other words-, assess what elements if any are worth continuing and what must be discarded... or sit at this juncture and declare the end of history. But while the game might be declared over, problems ensued.

The problem began when we forgot that our hand was covering the sun. When it wasn't forgetfulness, it was an anger at the sheer existence of a sun. What accounts for this lapse of judgement? We simply forgot about the function of artifice in argumentation. To make any point, one must do at least a small degree of injustice to alternative viewpoints, accentuating some, diminishing others. Participants in debate tacitly concede this reality as a lovely social grace. This is the norm. We exit the norm when we ignore or abuse the functionality of artifice. Another word for this is war, as expressed and universally accepted in Sun Tzu's famous epigram, "All warfare is based on deception." Artifice has a wide range of definition, its latin root relating it to art in all of its benign glory and the dictionary begins with "...clever or cunning devices or expedients, especially as used to trick or deceive others...". Homer applied artifice both to Hephaestus, the artistic/craftsman god and to Odysseus' use of deception in battle. In the former case, artifice is transparent and in the latter, concealed. When we forgot that we had concealed the sun of painting, we deceived ourselves -when in reality we thought we were deceiving others.

Credit goes to a majority of artists who painted after the beginning of the 90's, ignoring the proscription against painting. However a number of them made sure to continue to send signals of painting's diminished status. Wan, gloomy, strained, exhausted, limited, expended, constrained, cynical, the spreading delta of a negatory river course ever dissipating asymptotically. The better course for artists who resumed painting at that time would have been a forensic dive into the death of painting narrative, to search for sparks of vitality and animation. Side stepping allowed both narrative and counter-narrative to simultaneously exist blithely. As such, painting developed variants without theoretical support aside from a vague representation/abstraction distinction and concurrently, postmodern theory's balloon began to slowly leak away.

By the end of the aughts, aggressively bland painting -zombies- were selected by the marketplace for preeminence, successfully eclipsing the function of critics in debates over quality. The shrug by critics after the world historical sea change was reciprocated by the diminished power of criticism to influence the art world, their function implicitly negated as well by the end of history narrative. They acquiesced and were therefore nullified. Ideas stopped trafficking and therefore morality stopped as well, and finally all that was left standing was power. Money, in other words. What is a better expression of sheer power than the singularly minded zombie, hungry for the healthy brain? But here is the worrisome detail: Mugar coined Zombie-ism in 2014 and while the term trafficked in the art world dialog for a time, complacency has returned.

Now that symptoms are charted and a possible diagnosis if proffered, a cure is left begging. If we are living in dissipating times, and it is certain that we are to the point of schizoid mutual alienation, then its high time for the pendulum to swing back into the corrective direction. Conflict in the absence of reconciliation is another description of hell. The delta spread must at some point give way to the congealing force. Therefore, the synthesis of the thesis of modernism and the antithesis of postmodernism must in some way be the key for a succeeding 21st century. If modernism was a search for new orders that incorporated the proliferating categories of an erupting modern world and postmodernism embraced rupture, then one possible path forward, perhaps the only path forward, is a way to fuse system and schism simultaneously.

It is curious that the Roman god Janus in an anomaly in world history. This god of beginnings and passages, of change and time, has no analog in the Greek pantheon and it is the conceptual embodiment of an idea that had spawned no successors after the Roman Empire. What we need today is a supra-modern conception that incorporates the successful aspects of the preceding epoch in both aspects. The peculiar dualistic narrative of Southern California holds a special key that could help resolve the impasse and end the torpor of late stage postmodernism.

California art has long been identified with Light and Space, for good reason. The endless blue sky, the constantly amiable temperature, the particular microclimate where the desert meets the sea that creates a third dreamy environmental distinction. The West was and is the refuge for romantics, a frontier free from the burden of history. As Manhattan minted minimal and conceptual art, Southern California manifested a concrete version of the ethereal, one that could be witnessed by anyone first hand simply with the tilt of the head towards the bounded and boundless atmospheric cornea above.

Dreams aren't always benign. Close readers of SoCal historian Kevin Starr will note the abiding theme of boom and bust, of enticing dreams and ruinous catastrophe. Hollywood popularized film noir and Bukowski rescued John Fante with his introduction to "Ask the Dusk", and Nathaniel West's "Day of the Locust" focused on the losers of the casting lottery. The dream state isn't always so sweet.

However, pain has a tendency to fade from the mind given the passage of time. As a result, the halcyon image of California as the natural home of Light and Space was well on its way to cementing itself in the popular imagination by the end of the 80's. Of the dozens of art schools in the region, CalArts was leading the way during this time toward its own version of Light and Space, dematerializing studio practice and uploading theory into the clouds. Bibliographical citation and required reading reoriented to a mental/conceptual ethereality -another kind of Light and Space- in all art schools feeding into the local population. The art world seemed happy to shed its mortal coil. Then in 1992, Paul Schimmel curated MOCA's landmark "Helter Skelter: LA Art in the 90's". Finally, the full dimension of SoCal could again be appreciated worldwide and a categorical home was established in the art history pantheon for artists such as Chris Burden, Llyn Foulkes, Mike Kelly, Paul McCarthy, Lari Pittman and Charles Ray among others. Utopia and dystopia was reunited in the popular imagination, again if only for a moment, in the popular imagination as two manifestations of the same state. Hester Skelter was nested within even larger watershed moments of world historical proportions. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989 and the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991. It was the end of the Cold War and it was effectively the end of the 20th century, a decade early. Postmodernism too, had run its course but no one in the art world could acknowledge this because we were then too deep within it to circumscribe its extents.

Dreams can be sweet or horrible, but they are neither one or the other entirely. Similarly, western civilization is already a composite of oppositional forces and as such the key to its extraordinary success is already in our possession. We must shrug off the propensity to forget the other when we are in the thrall of one. It is the nature of painting to reconcile opposites. Binder and solvents. Abstraction and representation. Value and color. The problem of painting since the 90's is that it had proceeded en passant after the narrative of the death of painting. This is probably the greatest insult to Critical Theory and late postmodernism, which deserved an intelligent rebuttal. By carrying on obliviously, painting proliferated a chaos of types, adding to an inchoate delta devoid of any critical purchase. The other duality of body and mind both need sleep. Sleep is restorative. Dreams are either incidental or crucial depending on one's world view, but whatever one thinks, dreams are integrative.

Binder and solvent, when mixed with agitation, form an emulsive body of paint. The corpus of paint resides within its own liquid universe of strength integrating the tensile and compressive. Like breaking and riding horses, paint resists human will until that intention understands its nature implicitly. Liquids are evasive, running, pooling, dripping. Less liquid yields the paste of impasto towards a maximum surface tension at odds with its own mass. Curvilinear geometries rule and when tools lift out of the mass, conic sections define. Painting navigates the dualities of the pulling distinctions of drawing and pooling erasure. Images are made known, or left to be apprehended, another conjoined duality of representation and abstraction. Like the accomplished equestrian, a good painter has a feel for the medium, an affection and pride in the healthy exercise of its nature.

The death of painting only worked as theatre, when both audience and actors could suspend disbelief, when the devices of murder were mere dramatic props. Only by seeking to understand when and why we went wrong in mistaking art for life, when we thought literally that progress could exterminate painting in art, can we move forward and conserve what was gained by that theatrical leap of imagination and build upon it towards the looming epoch already upon us.

February 14, 2019

Review Panel

ArtCritical's Review Panel met again last night. Editor and Publisher David Cohen hosted the evening, joined by Jonathan Santlofer, Nancy Princenthal and Lee Ann Norman. Shows under review include:

- R. H. Quaytman: "+ x, Chapter 34"

- Brenda Goodman: "In a Lighter Place"

- Dana Schutz: "Imagine Me and You"

- Shahrzad Changalvaee: "In Absentia, In Effigie"

I took notes...

February 8, 2019

Notebook: Opening Tomorrow

56 Henry Street

(between Market and Catherine)

Chinatown, NYC

56 HENRY is pleased to present Notebook, an exhibition curated by Joanne Greenbaum. Comprised of over 70 works, ranging from lists and diagrams, to small drawings and torn out sketchbook pages, Notebook showcases an index of items culled from artists' processes. The installation of works will be on display from February 9th through March 31st, 2019. Notebook is 56 HENRY's first group exhibition, and second collaboration with Joanne Greenbaum.By prompting artists to submit one "notebook drawing," or work that they, "would never show to a dealer or pull out during a studio visit," Greenbaum has created a unique context for works that were not meant to surface from the studio; Here, artists' forgotten pages, afterthoughts, and sentimental treasures are put on display. The resulting collection offers a glimpse into the messy, candid, scrappy, witty, and seductive range of thought that is accumulated in the process of making.

Joanne Greenbaum is an artist based in New York City. Over the past twenty years, her work has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, both in the United States and abroad. Most recently, Tufts University Art Galleries at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, MA mounted Joanne Greenbaum: Things We Said Today, a comprehensive solo exhibition that travelled to the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, CA. Greenbaum's upcoming exhibitions include solo presentations at Richard Telles, Los Angeles, CA in April 2019 and at Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York, NY in November 2019. Greenbaum is represented by Rachel Uffner in New York.

Among the artists included are Bill Adams, Marina Adams, Lucas Ajemian, Polly Apfelbaum, Karen Arm, Monika Baer, Heike Kati Barath, Erica Baum, Lisa Beck, Andrea Belag, Jean-Baptiste Bernadet, Ellen Berkenblit, Wolfgang Betke, John Born, Lizzi Bougatsos, Strauss Bourque-LaFrance, Katherine Bradford, Kerstin Bratsch, LaKela Brown, Edgar Bryan, Sedrick Chisom, Susan Cianciolo, Martha Clippinger, Jennifer Paige Cohen, Gianna Commito, Sarah Crowner, Carl D'Alvia, Paul DeMuro, Steve DiBenedetto, Lydia Dona, Cheryl Donegan, David Dupuis, Austin Eddy, Sally Egbert, Franklin Evans, Lauren Faigeles, Jesse Farber, Rochelle Feinstein, Amy Feldman, Ali Fitzgerald, Ryan Foerster, Hermine Ford, Monica Forrestall, Al Freeman, Joe Fyfe, Nikita Gale, Kate Gilmore, Robert Goldman, Tamara Gonzales, Wayne Gonzales, Ethan Greenbaum, Rashawn Griffin, Monika Grzymala, Tamar Halpern, Rand Hardy, Kylie Heidenheimer, Mary Heilmann, Matthew Higgs, Eli Hill, Chris Ho, Dennis Hollingsworth, Maryam Hoseini, Jim Hyde, Shara Hughes, Sam Jablon, Pablo Jansana, Jasmine Justice, Shirley Kaneda, Deb Kass, Dennis Kardon, Betsy Kaufman, Matt Kenny, Jon Kessler, Rosy Keyser, Anya Kielar, Polly King, Elisabeth Kley, Jill Levine, Markus Linnenbrink, Pam Lins, Britta Lumer, Lauren Luloff, Matt Magee, Marta Marce, Max Maslansky, Saira McLaren, Suzanne McClelland, Rebecca Morris, Jill Moser, Robert Moskowitz, Sam Moyer, Lauren Muller, Kate Newby, Cady Noland, Mira O'Brien, Alix Pearlstein, Sheila Pepe, Janine Polak, David Rhodes, Halsey Rodman, Andrew Ross, Dieter Roth, Heather Rowe, Adrianne Rubenstein, Jackie Saccoccio, Lin May Saeed, Sally Saul, Hal Saulson, Mira Schor, Carole Seborovski, Michelle Segre, Mary Servane, Arlene Shechet, Kate Shepherd, Amy Sillman, Cary Smith, Agathe Snow, Jennifer Steinkamp, Cynthia Talmadge, Richard Tinkler, Patricia Treib, Ryan Wallace, Susan Wanklyn, Bradley Wester, Ben Charles Weiner, Matthew Weinstein, Anna Weyant, Roger White, Wendy White, Jesse Willenbring, Jesse Wine, Randy Wray, B. Wurtz, Tamara Zahaykevich, Peter Zohore, Kevin Zucker, Molly Zuckerman-Hartung and more.

February 3, 2019

James Kalm Rough Cuts on Burgeoning

It's a real NYC honor to have a show covered by Loren Munk's James Kalm / Rough Cuts.

Burgeoning with gratitude.